Western Cape Government

Biomimicry SA

The project has been suspended

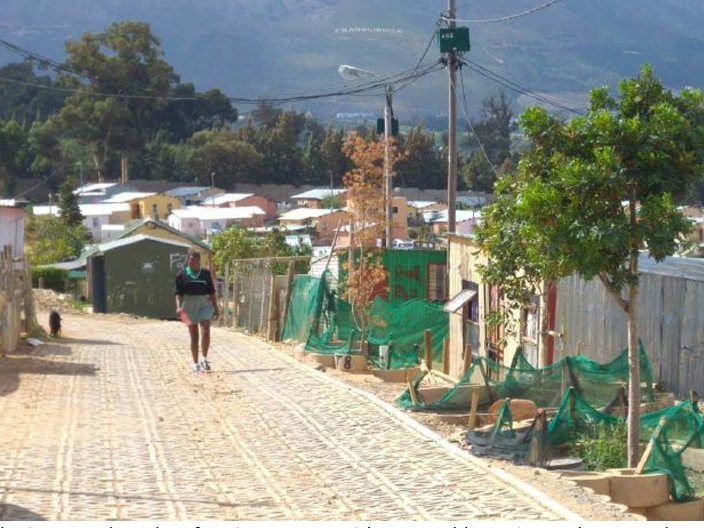

The Genius of SPACE project in Langrug informal settlement near Franschhoek was part of the Western Cape Government's (WCG) 110% Green Initiative. It was developed in collaboration with the Berg River Improvement Plan (BRIP) to address pollution from informal settlements along the Berg River. At the time of the project, the population of Langrug was between 4,000 and 5,000, with nearly 2,000 informal houses. Although water, sanitation, and bulk services are provided in Langrug, these services are not universal and have led to the disposal of wastewater and solid waste on open ground throughout the settlement. This forms foul-smelling puddles or flows downhill into the Berg River, an important resource for agricultural exports and fisheries in the Western Cape. The initiative aimed to improve human and ecological health, economic development and quality of life for Langrug residents by applying and testing biomimicry principles. Key role players included the Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning, Isidima and Greenhouse Systems Development.

In Langrug, the absence of piped sewerage, limited municipal services, and lack of hardened surfaces led to the accumulation of dirty water and solid waste in public spaces, resulting in localised flooding and health risks such as childhood diarrhoea. Furthermore, inadequate solid waste collection led to informal drains becoming blocked, creating stagnant water in the settlement. The project sought to apply a bottom-up approach that empowered community members to develop simple, practical solutions for improving their living conditions while also promoting social development. A range of biomimicry principles inspired by nature’s methods of water purification and waste management were applied. Beyond addressing pollution, the initiative also aimed to stimulate local enterprise and job creation. The initial phase focused on constructing greywater disposal points fitted with sieves to prevent blockages. These disposal points are connected to underground pipes that channel wastewater through “living sewers,” consisting of planted swales and wetlands, before discharging into tree gardens. The vegetated sewers provided preliminary greywater treatment, while the tree gardens contributed to community greening. Adopting a systems-based approach, the pilot emphasised participatory co-design, community capacity building, and local ownership of solutions, supported by private-sector partnerships

The pilot project generated employment for 15 full-time workers, 11 of whom were Langrug residents. It also strengthened community agency by involving local residents directly in the design, planning, and implementation processes through a representative steering committee. The introduction of green infrastructure not only managed untreated greywater and reduced unpleasant odours but also restored a sense of dignity and enhanced the overall quality of life within the settlement. Furthermore, the initiative distributed wheelie bins to households to support solid waste collection and separation. More than 500 Langrug residents participated in the pilot project.

The project implemented 27 greywater disposal points (constructed from round blue drums), a network of underground wastewater pipes, permeable paving, and 15 tree gardens designed for water filtration and nutrient recycling. The underground piping system helped reduce local flooding and manage stormwater runoff, complemented by improved road surfaces and the installation of permeable concrete pavers. Additionally, “living sewers” were strategically positioned along vertical pathways between homes to enhance environmental quality and public health while slowing stormwater flow. The living sewers replicated natural processes by filtering water through planted swales and wetlands. This nature-based solution offers multiple benefits: it separates polluted greywater from stormwater, cleans and treats the water to improve soil quality, and contributes to greening the settlement.

Stakeholder engagement conducted over 2 years ensured buy-in from the local community for the pilot. Funding support from the Western Cape Government facilitated implementation.

Although the project concept was well received by community members—many of whom expressed interest in extending the initiative to other sections—the pilot concluded in 2018 and was not continued. This discontinuation resulted from budget constraints, administrative delays, challenges in cooperative governance, infrastructure limitations, and weak communication and coordination between the community and local government. As a result, the planned second phase, which aimed to generate income for the community, did not materialise.

A major obstacle throughout the project was the lengthy implementation period. Delays in securing funding, completing tender processes, organising design workshops, and maintaining community engagement eroded stakeholder interest and undermined the project’s sustainability. Moreover, the initiative did not adequately address the community’s higher-priority concerns, such as land tenure (given that the settlement is situated on municipal land) and employment opportunities, which were perceived as more urgent than greywater management.

Maintenance also posed significant difficulties. During implementation, community agents were tasked with maintaining the infrastructure and preventing blockages. However, once the pilot phase ended, newly planted trees were vandalised or stolen, disposal points became congested, and leaks led to improvised repairs like the dumping sand, which impeded the functioning of the system.

A key lesson from Langrug is that similar projects should dedicate a substantial portion of their budget to community and stakeholder engagement, which is often more critical to long-term success than physical implementation alone. Furthermore, financing mechanisms should be adapted to better accommodate the fiscal limitations of the public sector.